THE ENDLESS PAVILION

Art Omi Residency, 2019/ Work in Progress

Throughout his long career, Le Corbusier was one of the most vocal critics of the museum typology as a repository of the ‘high arts.’ In L’Espirit Nouveau, he calls for a public inquiry by proposing a heretical question “Should the Louvre be burnt?”[1] Again, at the Internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes (1925), Le Corbusier challenges the very concept of the museum, “The museum is bad because it does not tell the whole story. It misleads, it dissimulates, it deludes. It is a liar.”[2] In both these interventions and others, Le Corbusier’s diatribe was against the museum as a static, staid, highly curated and closed entity. The thought that royal authority could somehow mandate what is considered art, deeply infuriated Corbusier and led to his quest for a radically modern and open conception of the museum.

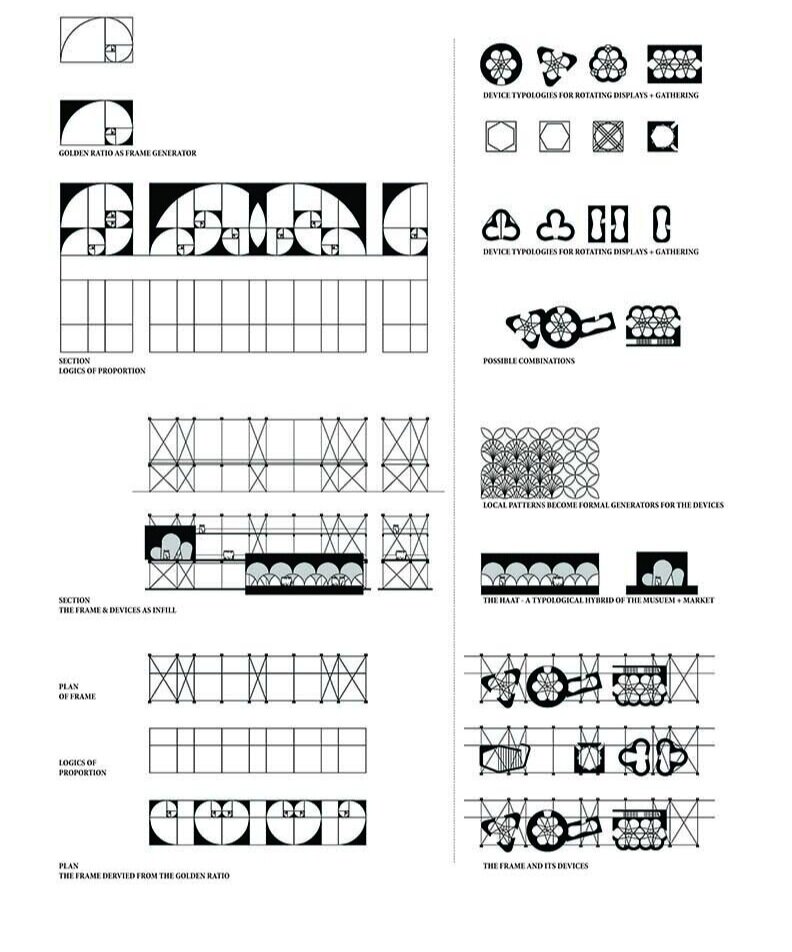

The museum for Le Corbusier is thus a utopian project where the unlimited accumulation of knowledge replaces its archaic function as a finite repository of artifacts. The search for the museum’s ideal form becomes a career-long preoccupation which begins with his early unbuilt projects: the Mundaneum (1929), and the Museum of Unlimited Growth (1931). These explorations culminate with three late career buildings - The City Museum in Ahmedabad (1954), The National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo (1959) and the Government Museum in Chandigarh (1968), the last of which was completed after his death. All three built museums are remarkably similar and have the same architectural genotype taken directly from the Museum of Unlimited Growth. They are all square introverted plans, where the ramp turns into a spiral folded upon itself. All have ‘no façade’[3] since their growth is ‘anticipated’. For the Museum of Unlimited Growth, Le Corbusier recommended that “a mason and a laborer be permanently employed in building this museum in an uninterrupted and perennial operation”. [4] The endless museum would be an endlessly incremental project – perpetually under construction. Yet, six decades later these buildings have become precisely the finite, static and conventional museum entities that Le Corbusier so heavily criticized – their collections closed, their futures staid. More worryingly, in the case of Chandigarh and Ahmedabad, their very existence is threatened by powerful real estate lobbies.

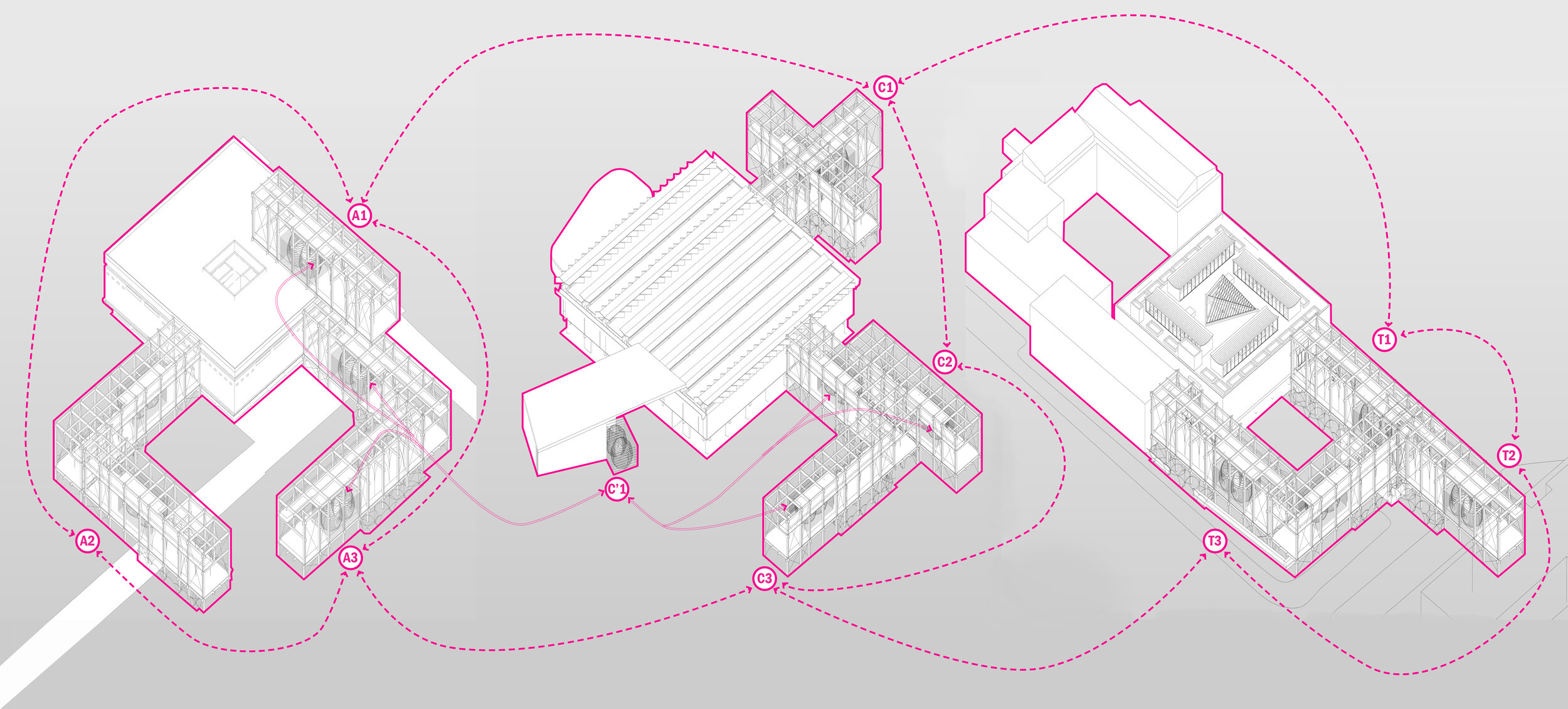

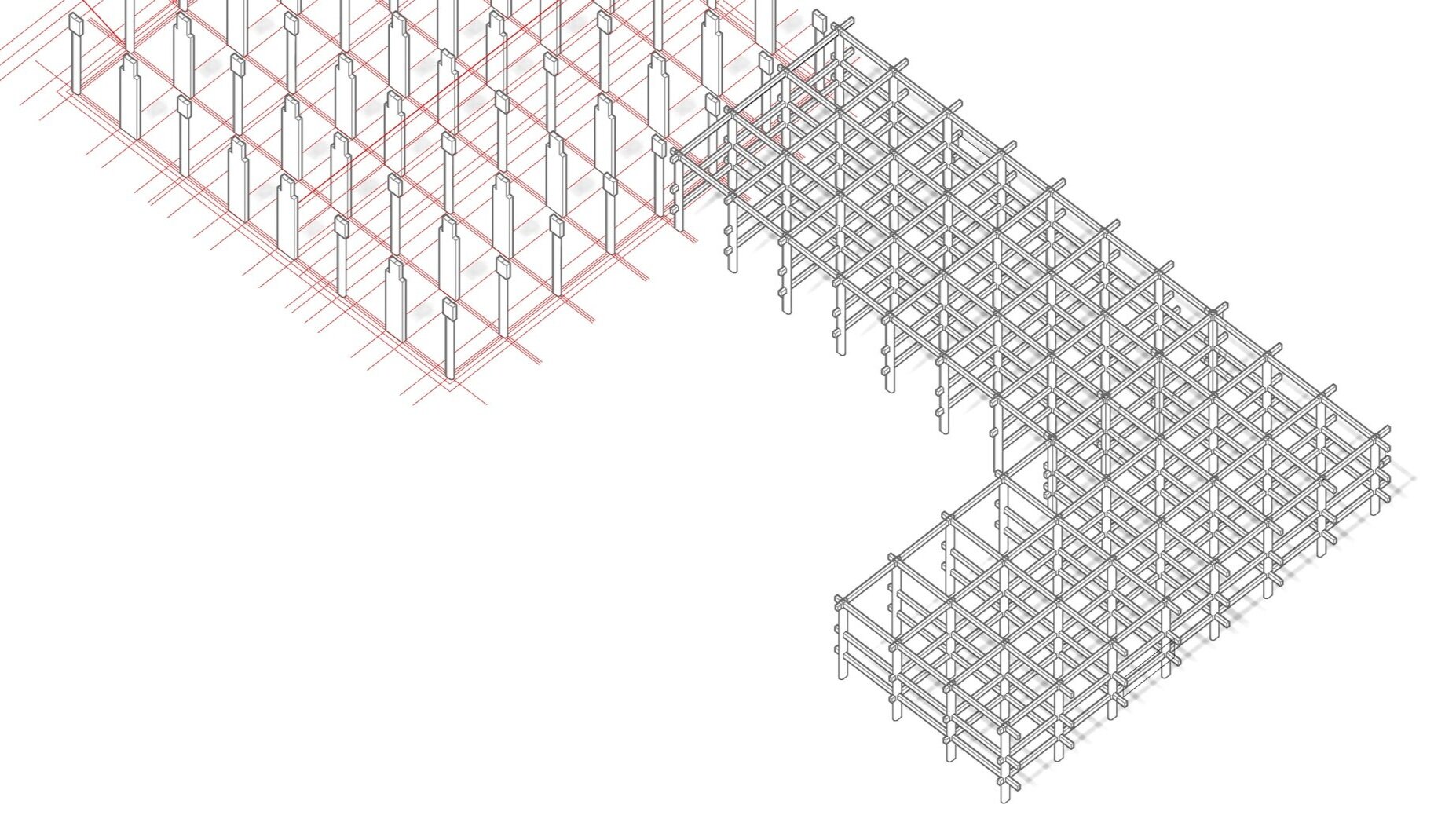

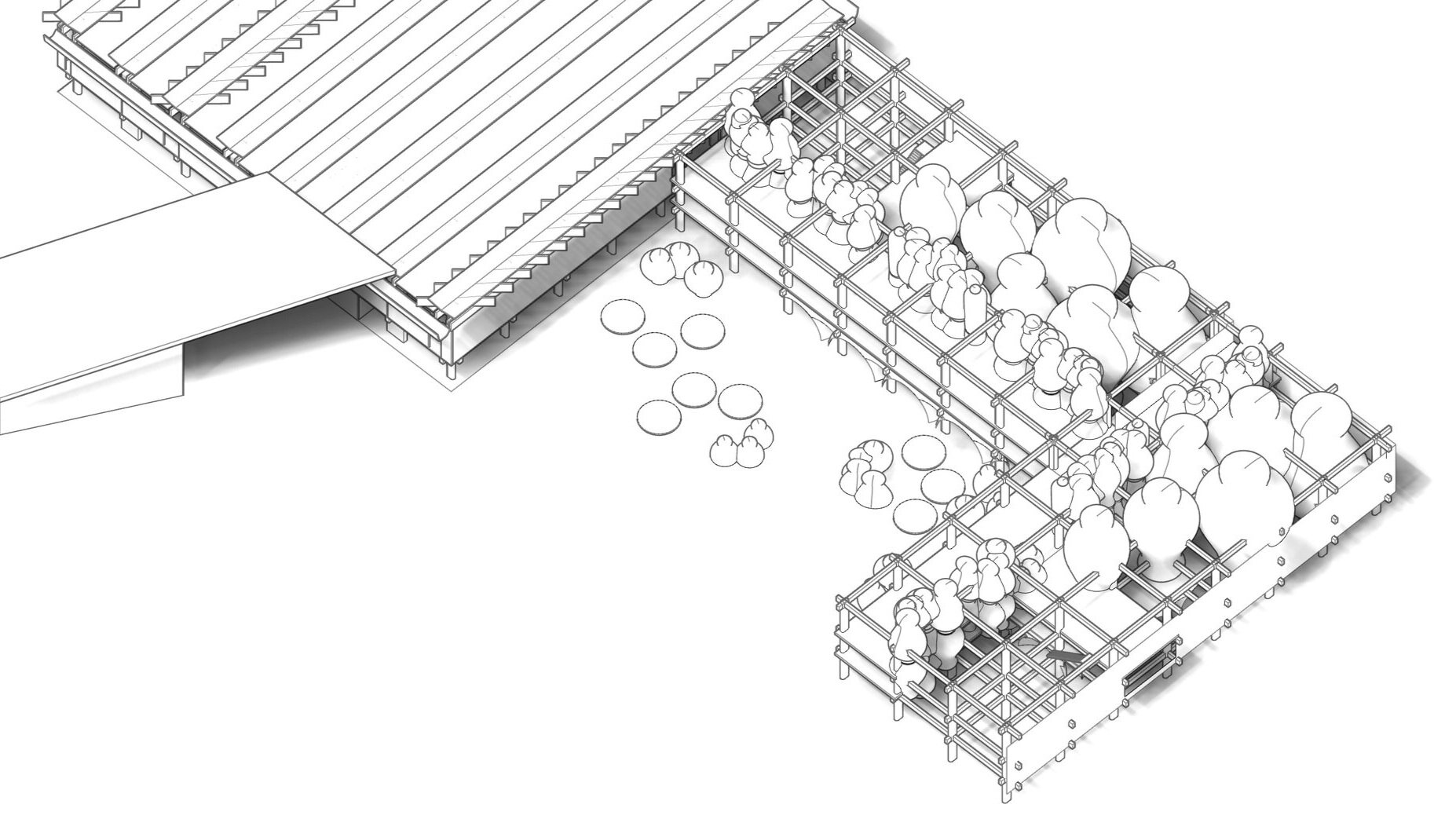

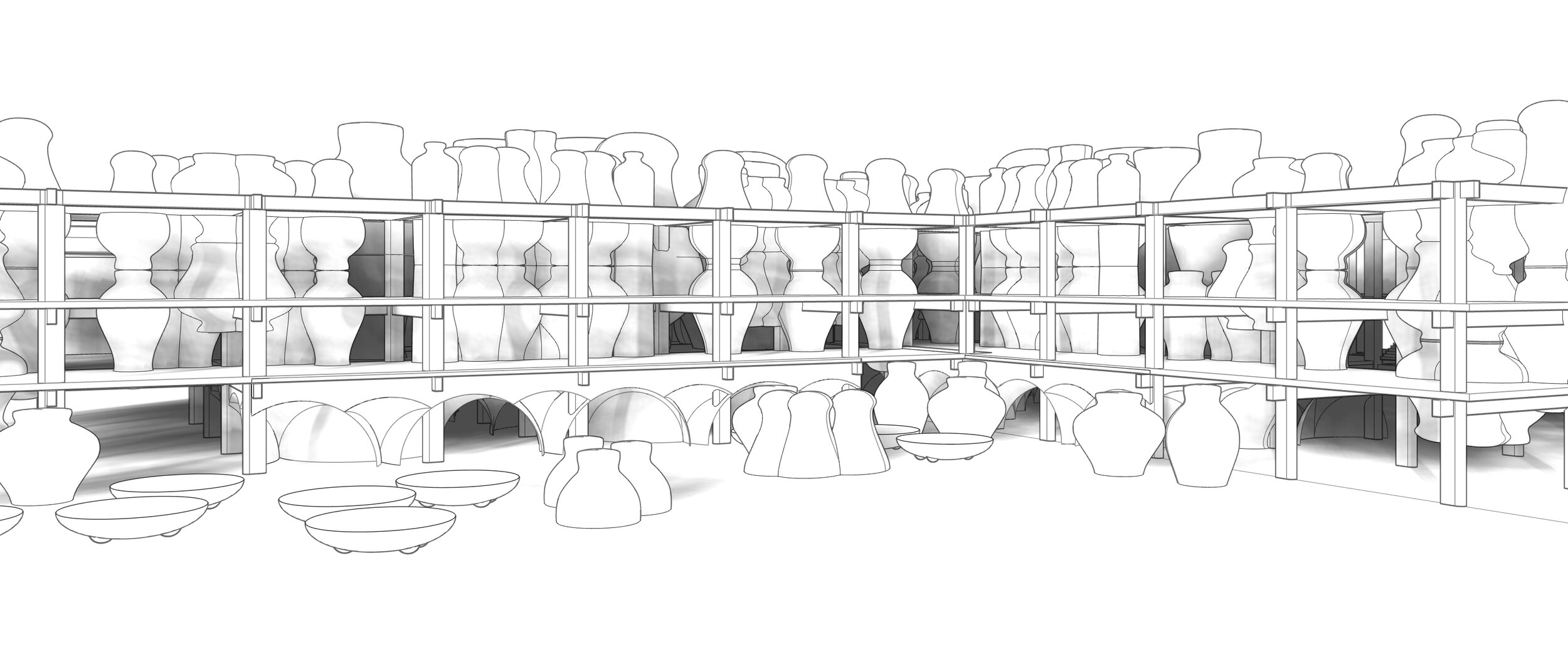

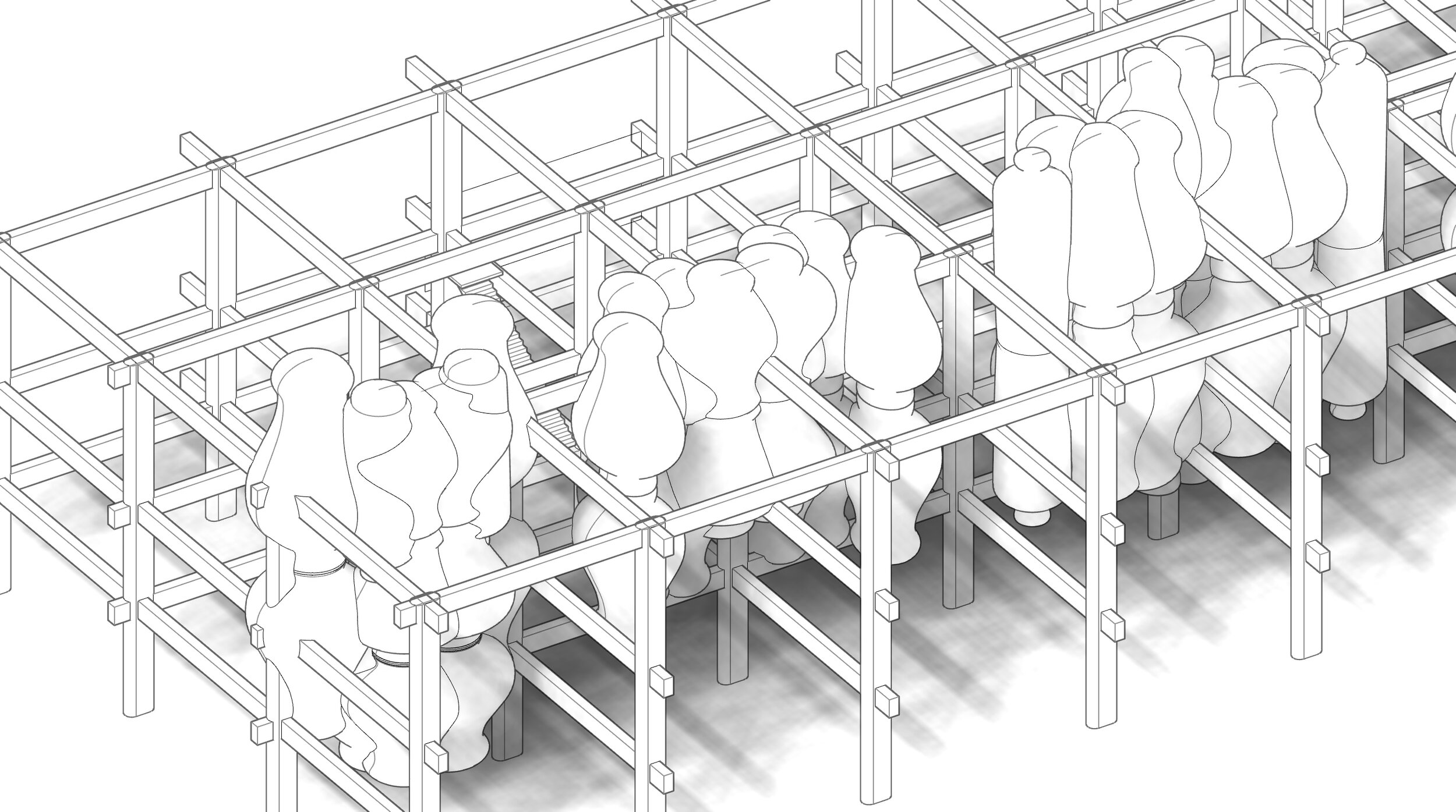

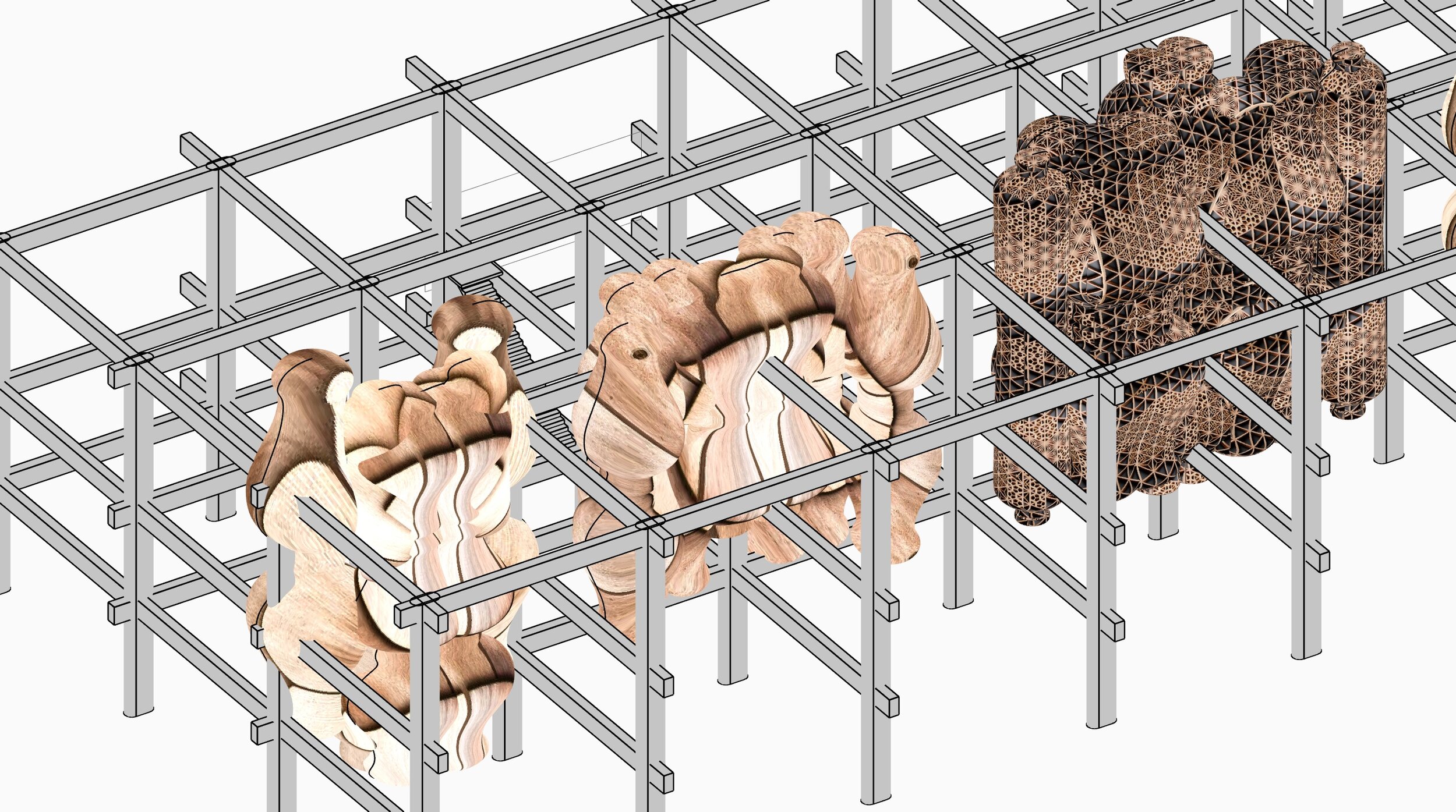

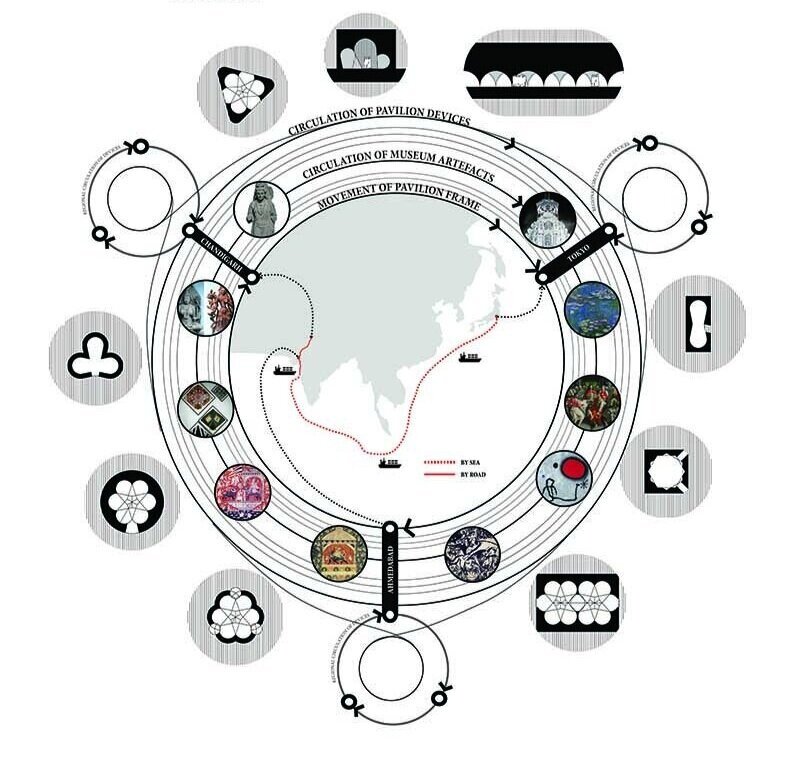

The fact that these museums arguably relate more to each other and to Le Corbusier’s conception of an endless museum than to their local contexts becomes a point of departure for a design proposal that seeks to rejuvenate these sites and revive interest in their collective histories as a means of both critiquing and preserving their invaluable modernist legacies. The project proposes an itinerant pavilion which will serve as a temporary attachment to each of the museums.

The pavilion will literally be transported across the three museum sites and be reassembled each time in a ritual of making and unmaking evoking a formative agenda of the Endless Museum. It will also stimulate their futures to projective, open-ended possibilities through rotating exhibitions, installations and staged events as the pavilion migrates between sites. Through its itinerant condition, the pavilion will serve as an agent provocateur activating key constituents, local stake holders, diverse publics as well as the larger community of artists and architects.

There a long tradition of the temporary pavilion as an artifact of enduring socio-cultural significance. In Japan, the Ise Shrine is demolished and rebuilt every twenty years on an adjacent site, in a ritual that has lasted for over a thousand years. This signifies the Shinto belief in the impermanence of things and also allows construction techniques to be passed from one generation to the next. India has a long and diverse tradition of pavilions being reconstructed during festivals at temple sites. There is a second attribute to the pavilion since the inception of modernism - as a medium of experimentation; a critical vehicle embodying the zeitgeist. (The Philip’s Pavilion and The Pavilion de L’Esprit Nouveau both temporary pavilions by Corbusier come to mind). Since its reconstruction in the 1986, the Mies van der Rohe Foundation has invited architects to temporarily alter the Barcelona Pavilion, through “interventions” that have kept the pavilion as a node of debate on architectural ideas. In more recent years, Shigeru Ban’s Container Museum (2002), a pavilion like structure built with shipping containers, was rebuilt on sites in Santa Monica, NYC, and Tokyo. The Young Architects Program has successfully replicated pavilions hosted at Queens MOMA PS1, with sites in Santiago, Istanbul, Seoul and Rome.

[1] Moos, Stanislaus von. Le Corbusier: Elements of a Synthesis. Rev. and expanded ed., 010 Publ., 2009.

[2] Le Corbusier quoted in Calum Storrie, The Delirious Museum: A Journey from the Louvre to Las Vegas, London: I.B. Tauris, 2006.

[3] Le Corbusier 1910-65, eds. W. Boesiger and H. Girsberger (Zurich: Editions d'Architecture, 1967), 2 36.

[4] Le Corbusier, My Work, trans. James Palmes, London: The Architectural Press, 1960, p. 101.